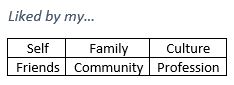

The book by this title from Sinan Aral suggests that social media might adapt their LIKE BUTTON to a set of six buttons to indicate the responder's impression that the post is liked by:

- "I as an individual",

- "My friends & I",

- "My family & I",

- "My community & I",

- "My culture & I", and/or

- "My profession & I".

This may seem like a benign (even superfluous) augmentation, but it's designed to shift awareness away from organism centricity to the wider range of social subsystem correlations that we'd like to nurture. Moreover, it will provide data on the shifts in focus that a given post elicits in that post's audience.

Thus for example posts that elicit a focus on politics when the topic is some natural process (like a pandemic) that we need to bring technical knowledge to bear on will automatically show up as a professional topic with few professional likes. Likewise when experts (say in astronomy) make assertions about elements of culture with which they have limited experience.